Observations on the difficulties of Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) on their way to the mass market.

Question-and-answer sessions at conferences can be a medium catastrophe, but a contribution at the Push Conference 2016 in Munich by Mike Alger inspired me in a surprising way.

After a lecture on VR, a participant from the audience asked the following question: What will it be like in the future, when people meet at the same place, but experience a technologically souped-up, possibly completely independent world in which everyone unwinds their own program? How do we communicate with each other when we no longer perceive the same thing and a place of encounter no longer has the same face for everyone?

The following answer of the speaker: With digital products this has been happening for years anyway. No Facebook feed is like any other, personalized offers differ significantly in terms of content, and yet we find a common language.

In fact, Facebook was one of the first platforms to be built on delivering content to users that was tailored to their expectations. This introduced a new form of differentiation, which no longer relies on creating a place that serves every visitor in the same way, but rather on changing this place according to their needs (although I sometimes wonder how well Facebook knows me, given the irrelevant advertising). Augmented Reality is on its way to transfer comparable things to real places: the player sees an arena at an art monument, in which he can compete with other gamblers, the art lover can gain insight into the creation of this object by additional information.

In contrast to the enrichment of reality through Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality currently still lacks the promise to "depict reality" in almost every respect. Despite great efforts, the idea of reaching broad masses with VR products currently seems to be rather fictional. Far away from the holodeck known from Star Trek, we are moving - tied to the console in a tangle of cables - through virtual worlds that like to cause headaches and nausea. When simulating reality, there is usually little freedom and the possibilities for action correspond to those of a simple point-and-click adventure.

At this point, a look back: a few years ago, 3D cinema also offered a promising perspective for consumer electronics; new technical possibilities opened up expanded spatial experiences. What still seems attractive for many visitors in a darkened cinema hall does not work in their own living room: a common TV evening with annoying 3D glasses was largely rejected by the people, the consequence: 3D does not really play a role in the current TV landscape anymore. The obstacle of a simple aid, such as glasses, prevented the widespread breakthrough of a technology in the private sphere.

A similar development could be imminent for VR in the near future: The interested parties turn away from the technology, which is perceived as the stigma of lonely technology freaks in their own world and does not allow a common experience. Only when the necessary technical aids become invisible and common playgrounds are possible, VR will become attractive for people who are not only keen on technical innovations.

Now we are not fooling ourselves: The assumption that we observe the same thing at the same place is a fallacy anyway. Our perception is too much influenced by what we have experienced, what is relevant for us and how we relate to our surroundings. The idea, however, that new digital tools will have a massive impact on essential factors of our lives, remains fiction for the moment. This is also because the benefits beyond entertainment and simulation offer people little added value worth mentioning.

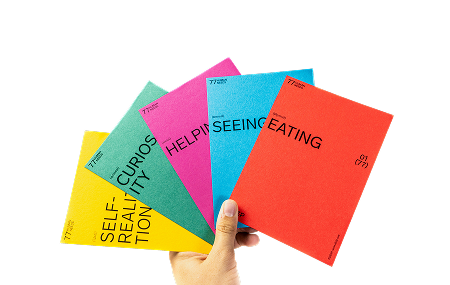

Image: Tom Galle

.jpeg)